Given the recent data breach and Coinbase’s user agreement that aims to force customers into arbitration rather than individual or class action lawsuits, it’s interesting to read the outcome of a recent arbitration case against Coinbase.

Customer lost $350,000 in September 2022 to a phishing attack from a scammer that the customer said had “confidential information that could have only been obtained with direct access to Coinbase’s database”.

Coinbase didn’t prevent the suspicious transfers, allegedly wiped customer’s transaction history, blamed the customer for the loss, then refused to reimburse. Arbitration concluded with $0 reimbursement.

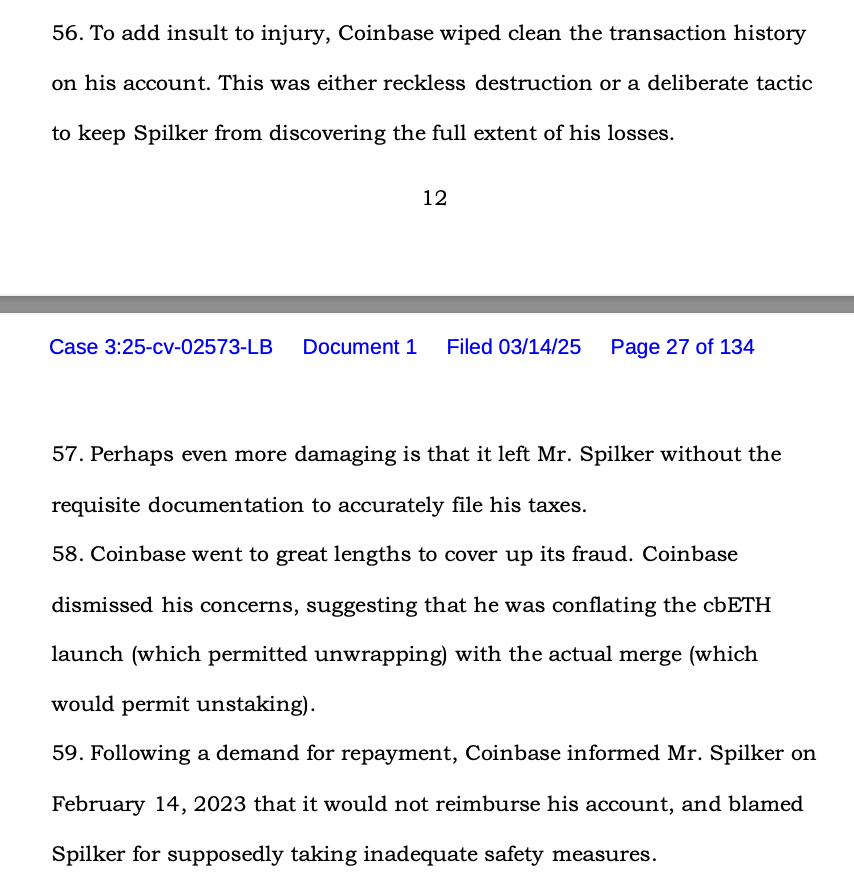

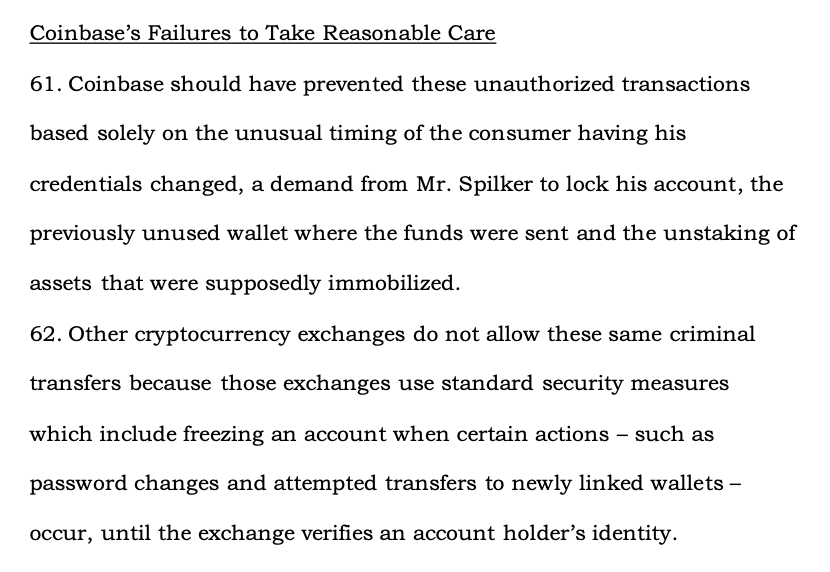

Arbitrator found the complaint had been filed too late, and that the customer had admitted that a third party rather than a Coinbase insider had performed the theft. Doesn’t appear the arbitrator investigated the claims of a possible breach, or how the hardware MFA was bypassed.

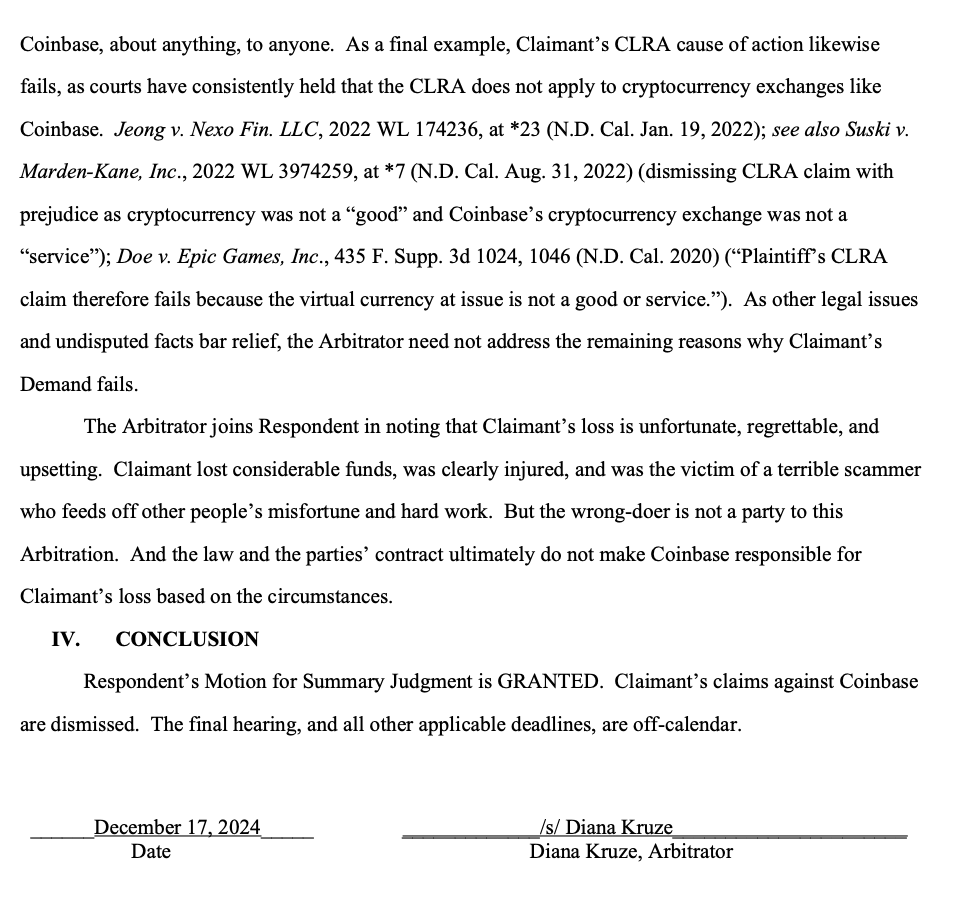

![9. On December 17, 2024, Arbitrator Kruze issued an Order Granting Dispositive Motion as to all of Mr. Spilker’s claims. Ex. A at 6 (“Respondent’s Motion for Summary Judgment is GRANTED. Claimant’s claims against Coinbase are dismissed.”). 10. The Final Award holds: a. Claimant’s EFTA cause of action is time-barred because the “one-year limitations period begins when the first unauthorized transfer occurs, not upon discovery by the consumer, and not when the consumer notifies the defendant of the unauthorized transfer.” Id. at 3, applying 15 U.S.C. §1693m(g) and Wike v. Vertrue, Inc., 566 F.3d 590,593 (6th Cir. 2009). b. “The undisputed facts show that a third party, not Coinbase, caused Claimant’s damages” and that “Claimant’s damages were the result of an intervening and superseding cause: the actions of a third-party scammer. Coinbase, as a matter of law, cannot be held liable for Claimant’s damages.” Ex. A at 4, citing May v. Google, LLC, No. 24-CV-01314- BLF, 2024 WL 4681604, at *10 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 4, 2024). c. The parties’ contract forecloses Mr. Spilker’s causes of action for breach of contract, negligence and tort claims, and claims under Idaho and Oregon law. Ex. A at 5. d. Pursuant to Melchoir v. New Line Prods., Inc., 106 Cal. App. 4th 779, 793 (2003), “Claimant’s cause of action for unjust enrichment fails because ‘there is no [such thing as a] cause of action in California for unjust enrichment.’” Ex. A at 5. e. Mr. Spilker’s CLRA claim fails “as courts have consistently held that the CLRA does not apply to cryptocurrency exchanges like Coinbase”. Id. at 6, citing various cases.](https://storage.mollywhite.net/micro/0bbcc42846cc232283eb_Screenshot-2025-05-27-at-1.04.40---PM.png)

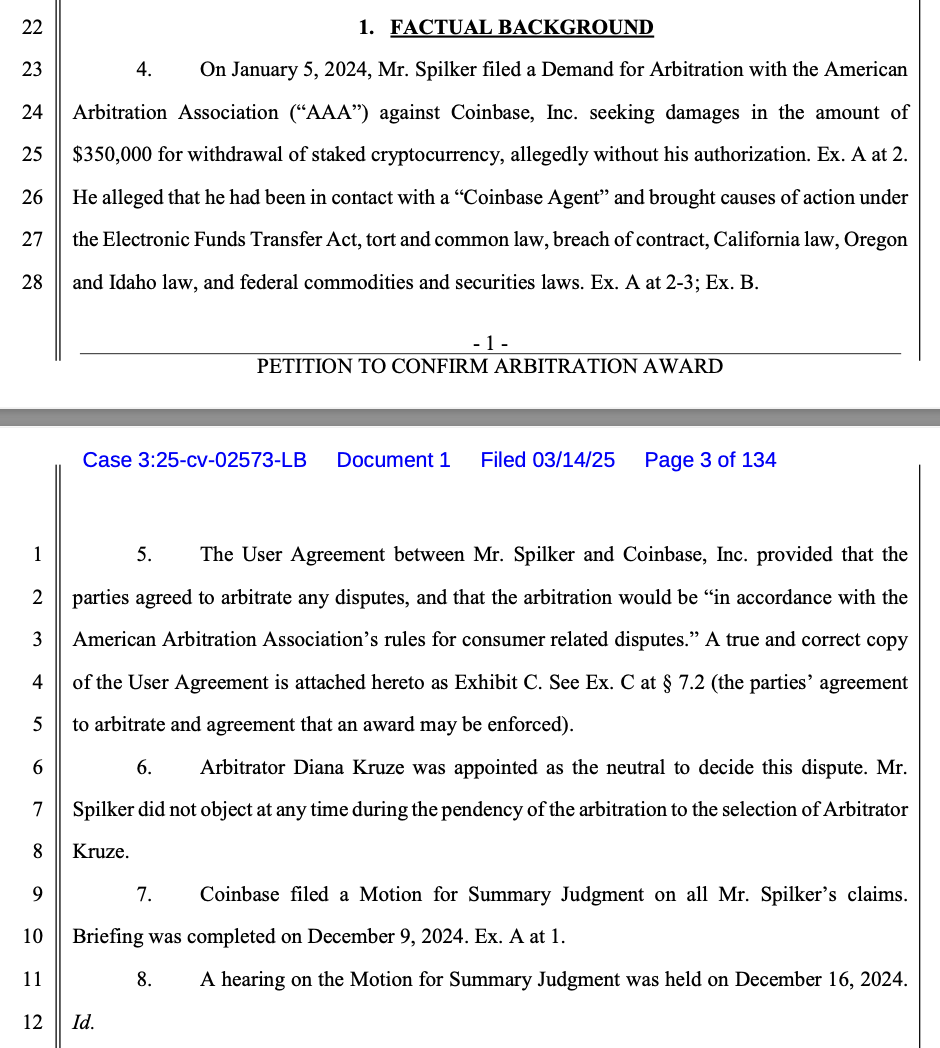

![Claimant does not dispute these facts in its briefing. In other words, Claimant’s damages were the result of an intervening and superseding cause: the actions of a third-party scammer. Coinbase, as a matter of law, cannot be held liable for Claimant’s damages. See May v. Google, LLC, No. 24-CV-01314-BLF, 2024 WL 4681604, at *10 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 4, 2024). Third, Claimant’s supplemental production also eviscerates many of Claimant’s other causes of action. For example, in his Demand, Claimant alleges that Coinbase never advised users that staked ETH could be wrapped and traded before his September 2022 loss. In its Motion and Reply, Coinbase previously relied on public statements announcing the launch of cbETH as early as August 2022. Claimant’s belated production, attached to Respondent’s supplemental briefing, also contains undisputed facts that Claimant was himself actually informed about cbETH’s launch before his funds were stolen. This disclosure significantly undermines Claimant’s misrepresentation claims under common law, securities law, and commodities law. Fourth, the parties’ contract forecloses many of Claimant’s causes of action. For example, Claimant’s breach of contract claim is undercut by section 6.6 of the UA, which explicitly apportions the risk of account compromises to Claimant as the user: “Any loss or compromise of . . . your personal information may result in unauthorized access to your Coinbase Account(s) by third-parties and the loss or theft of any Digital Assets and/or funds held in your Coinbase Account(s) and any associated accounts, including your linked bank account(s) and credit card(s). . . .We assume no responsibility for any loss that you may sustain due to compromise of account login credentials due to no fault of Coinbase.” Moreover, the UA’s choice-of-law provision in section 9.5 restricts Claimant to California law, foreclosing Claimant’s Idaho and Oregon-based causes of action. In addition, the UA and California law effectively cut off Claimant’s tort claims, such as his negligence cause of action. See, e.g., Berk v. Coinbase, Inc., 840 F. App’x 914 (9th Cir. Dec. 23, 2020) (Coinbase owes no independent tort duty of care beyond the promises made in the UA). Finally, there are other independent reasons why Claimant’s Demand cannot succeed. For example, Claimant’s cause of action for “unjust enrichment” fails because “there is no [such thing as a] cause of action in California for unjust enrichment.” Melchior v. New Line Prods., Inc., 106 Cal. App. 4th 779, 793 (2003). As another example, Claimant submitted no evidence of any false statements made by](https://storage.mollywhite.net/micro/cb92d9a3b3a2046762ee_Screenshot-2025-05-27-at-1.13.11---PM.png)